Case study: Scaling an app

2018-09-05

Source:vignettes/case-study-scaling.Rmd

case-study-scaling.Rmdshinyloadtest and shinycannon are tools to

help you assess your application’s performance. Since they are only

tools to measure performance and not to improve it, they must be used as

part of a larger workflow.

In this case study, we’ll introduce a workflow — the optimization loop — and apply the workflow to the process of optimizing the cranwhales demo application.

For a lighter treatment of shinyloadtest that will get

you using it faster, you may consider starting with the

introductory tutorial instead.

The Optimization Loop

The optimization loop is a general methodology for approaching

optimization work. Applied to the problem of capacity optimization,

which is the area shinyloadtest is helpful in, the steps

are defined as:

-

Benchmark: Pick a number n, how many users

your application must concurrently support. Simulate n users

interacting with your application and collect latency metrics. Use

shinyloadtest::record_sessionto record a realistic interaction, and theshinycannontool to simulate n users performing the recorded interaction. -

Analyze: Visualize and interpret the metrics.

shinyloadtest::load_runsis used for this part. If it looks like n users can be supported, stop here. Otherwise, go to the next step. - Recommend: Based on analysis, propose a way for the capacity of the application to be increased. Patterns in the metrics can help you identify what change in the application or its configuration would be most beneficial. It could be a code change, like converting the app to async, or a configuration change, like increasing the number of R processes allocated to the application in Posit Connect.

- Optimize: Implement one or more of the recommendations and benchmark again. Repeat the process until the application supports n users to your satisfaction.

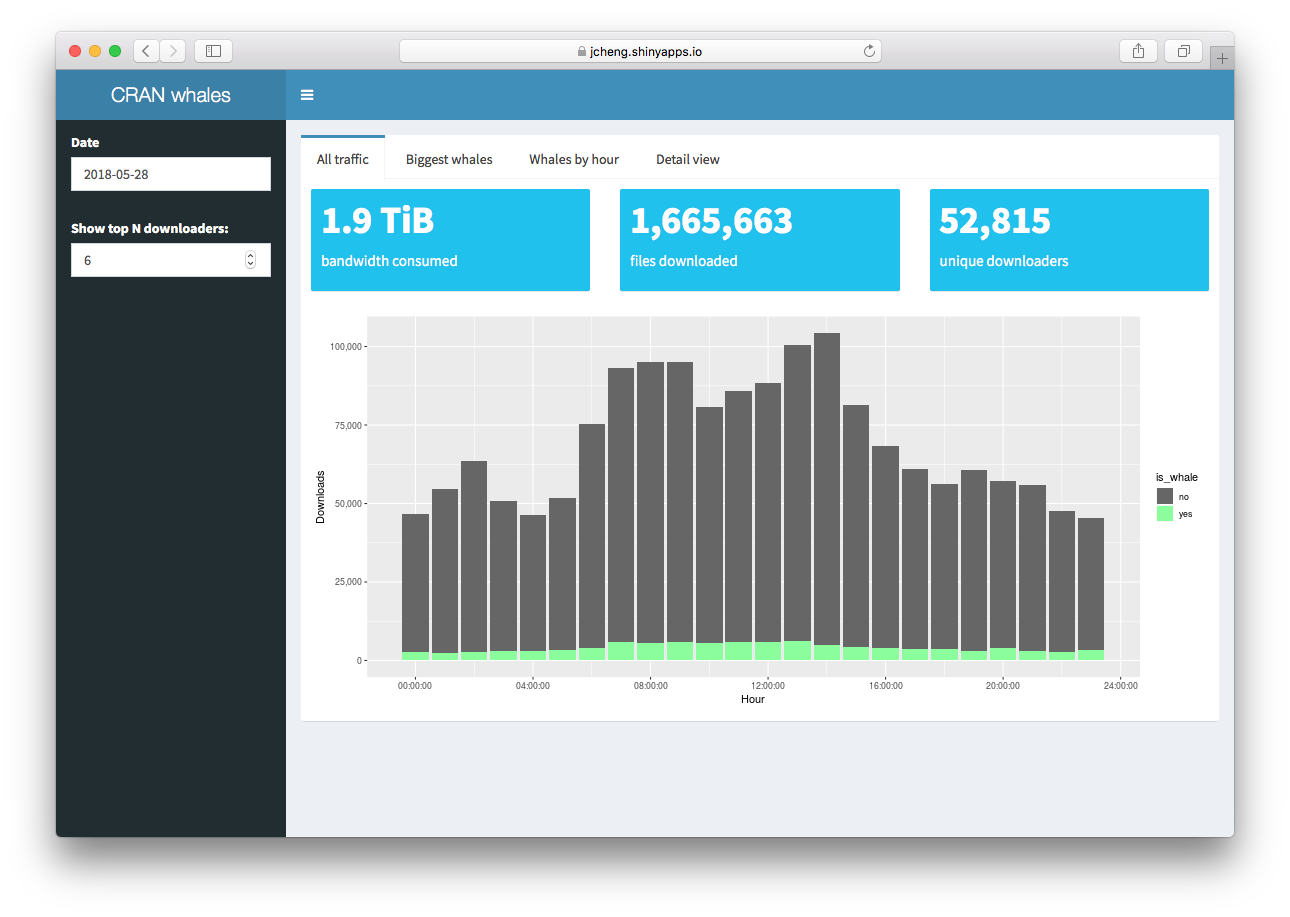

The cranwhales demo app

For the purposes of this case study, we’ll pretend that cranwhales is an app we

wrote and that we’re interested in ensuring it can support a minimum

number of concurrent users. In a nutshell, cranwhales is a way to

visualize anonymized download statistics from Posit’s

0-Cloud CRAN mirror. For more on the app’s features, see the

tour.

cranwhales was written by Joe Cheng to demonstrate Shiny’s async capabilities. We use it here because it’s close to a typical Shiny app in size and scope, and because it’s already given an optimization treatment in Joe’s async case study.

Joe’s case study focuses on the optimize step and

the mechanics of improving performance with an emphasis on using async

to do so. Here, we’ll instead focus on the benchmark

and analyze steps as enabled by

shinyloadtest and shinycannon.

Deployment

cranwhales is currently deployed on

shinyapps.io, but we’ll assume for this case study that you’ve

deployed cranwhales to your own Posit Connect

instance with default runtime/scheduler settings.

shinyloadtest is capable of benchmarking and generating

load against apps that require authentication

but we’ll assume your deployment of cranwhales is accessible without

authentication.

Benchmark

The first step is benchmarking, and we’ll do it in several sub-steps:

- Record a realistic session using

shinyloadtest::record_session - Run

shinycannonwith 1 user, producing a directory of “baseline” metric data - Pick a number n, the number of users we want to be able to use the app at the same time

- Run

shinycannonwith n users, producing another directory of metric data

Record a session

First you should install the shinyloadtest R package if

you haven’t yet:

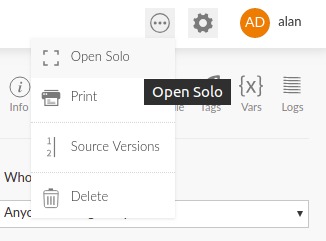

devtools::install_github("rstudio/shinyloadtest")Next, obtain the “solo” URL of the deployed app in Posit Connect. You can do this by navigating to the application from the list of published content, clicking the circular button at the top right of the screen, and then clicking “Open Solo”. This will open a new window. Copy the URL from this new window.

Back in the R console, run record_session with the solo

URL as an argument:

library(shinyloadtest)

record_session("https://rsc.example.com/content/1234/")This starts a local web server listening on

http://127.0.0.1:8600/ and should also open a new browser

window to this URL. This local web server is a proxy that relays content

to and from your Posit Connect instance, recording interactions so that

they can be played back later. It’s in this window that you should model

what you imagine would be a typical user interaction. Click around,

change things, and observe new outputs.

Do this for 1-2 minutes. When you’re done, close the browser tab. You should notice the function return in the R console.

On disk, in the directory where you started R, will be a new file:

recording.log. There may also be other files like

recording.log.post.0. These complementary files are created

when you upload files or if you use an htmlwidget like DT that uses HTTP POST to send

data.

Together, these files constitute a recording. They

are the input to shinycannon.

Baseline run

Now that you’ve made a recording, you’re ready for your first

shinycannon run. For the first run, you should just test

with 1 user. This will generate metrics analogous to those you

experienced when you made your recording, and will serve as a baseline

for subsequent runs.

Note: It’s best to run shinycannon on a machine close to the target machine on the network. We don’t want Posit Connect and shinycannon to contend for resources on the same machine.

In the directory where your recording.log* files are,

run shinycannon like this:

shinycannon recording.log https://rsc.example.com/content/1234/ --workers 1 --loaded-duration-minutes 5 --output-dir run1-

recording.logis the recording to use -

https://rsc.example.com/content/1234/is the “solo” URL of the target application -

--workers 1means to simulate one user -

--loaded-duration-minutes 5means each user should continually “loop” through the recording for at least 5 minutes after all workers have started. Since our recording is about a minute long, for this run we’ll collect metrics for about 5 iterations of the recording. -

--output-diris the directory to populate with metrics and run metadata.

Note: The command to run shinycannon might be different on your platform. For alternatives, see the shinycannon instructions

Once shinycannon has started, you should see output like

the following:

2018-08-31 00:22:11.009 INFO [progress] - Running: 0, Failed: 0, Done: 0

2018-08-31 00:22:11.010 INFO [thread00] - Waiting for warmup to complete

2018-08-31 00:22:11.011 INFO [thread01] - Warming up

2018-08-31 00:22:11.011 INFO [thread00] - Maintaining for 5 minutes (300000 ms)

2018-08-31 00:22:16.010 INFO [progress] - Running: 1, Failed: 0, Done: 0

2018-08-31 00:22:21.011 INFO [progress] - Running: 1, Failed: 0, Done: 0- Messages labeled

[progress]are status messages printed every 5 seconds until the run is complete. - Messages labeled

[thread00]are produced by the parent thread supervising the run, and contain information about state transitions. A run moves through 3 states as it progresses: warming up, maintaining, and cooling down. The warmup and cooldown periods are those during which workers are gradually starting or stopping. Maintenance is the period during which all workers are running, and its length is governed by the--loaded-duration-minutesoption.

Note: If you see any messages of severity ERROR, the run hasn’t necessarily failed, but the metrics it produces may not be usable. You should investigate the error and re-run. The

--debugflag will result in the creation of adebug.logfile in the output directory, which may be useful for debugging but can become large quickly.

Comparison run

Now that we have baseline metrics, we should conduct a more ambitious

run for contrast. Perhaps in our organization we can expect up to 5

people to use cranwhales at the same time, so to simulate that

possibility we’ll run shinycannon again with

--workers 5:

Load testing can be useful even if your target number is small, like 5.

shinycannon recording.log https://rsc.example.com/content/1234/ --workers 5 --loaded-duration-minutes 5 --output-dir run5Analyze

At this point we have two runs worth of metrics in our

run1 and run5 output directories. Let’s get

back in an R console and process the data into a dataframe:

library(shinyloadtest)

df <- load_runs("Run 1" = "run1", "Run 5" = "run5")With the data in a tidy data frame, we can generate an HTML report:

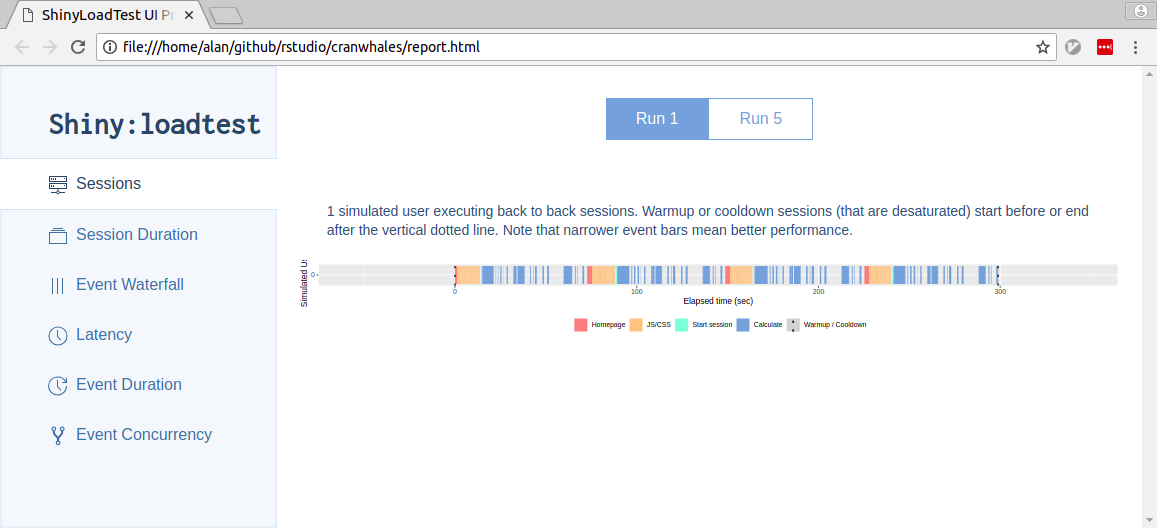

shinyloadtest_report(df, "report1.html")When you open report1.html in your browser, you’ll see

something like this:

If you don’t want to generate the report yourself, you can view an example here: case_study_report1.html

There’s a lot to take in here. If you’re interested in the meaning of everything you see, check out the analyzing load test logs vignette.

For now, let’s focus on the “Session Duration” tab. You’ll notice a tab bar at the top of the page that lets you quickly toggle between the Run 1 and Run 2 session durations. Here they are:

In each plot, time is the X axis and sessions are stacked atop one another on the Y axis.

On the first plot, we see 4 sessions, and each one completes roughly around the red line. The red line denotes the length of the recording. So, in the 1 worker run, the sessions seem to take roughly as long as they did for us to record. That indicates to us that the experience of using the application for these 4 sessions was similar to the one we experienced making the recording.

On the second plot, we see 12 sessions stacked, and the slowest one took roughly twice as long to play than it did for us to record. Many others also took significantly longer. This indicates to us a significant decrease in the responsiveness of the application as the number of concurrent users increases.

--workers 1resulted in 4 sessions, and--workers 5resulted in 12 sessions. Why is that? It’s because each worker repeated the recording as many times as it could in 5 minutes. So, the relationship between workers and sessions is one to many.

If your target number n is very large, you may find it easier to start by looking at the Latency tab which shows histograms of latency for the page load time and the latency of user interactions with the app.

Recommend

The application doesn’t seem to have performed well with 5 concurrent users, but it’s important to keep in mind that performance is relative to the kind of application you’re optimizing and to the needs of your users. If we do decide the app is too slow and we want to try to improve it, there are two courses of action we can consider:

- We could tune the app’s Posit Connect configuration. In this case, the easiest way to improve the performance in the 5-user case is to modify the app’s scheduler settings, dedicating 1 process per user and limiting the number of processes to 5.

- We could improve the performance of the application at the code level.

Dedicating more resources to the app is the easiest way to improve its performance, but it’s also the most costly resource-wise, and depending on what’s slow, might not even help. Dedicating your developer time is potentially costly in terms of your time, but improves the scalability of your app in the long run.

Throwing hardware at the problem is an easy fix in our case, but there’s usually a strong chance that it’s really easy to make your app dramatically faster with only small code changes. For example, you might just need to do some work once when your app starts instead of every time a reactive changes. Here are some resources for learning more about Shiny app performance:

-

profvis: In this webinar, Winston Chang demonstrates using the profvis package to efficiently identify and improve slow paths in code. - In this rstudio::conf talk, Alan Dipert describes the Shiny team’s efforts to improve the scalability of another demo app, CRAN explorer.

- In this other rstudio::conf talk, Joe Cheng describes how async can be used to improve the scalability of Shiny apps.

For the purposes of this case study, let’s say that we’re really busy, and it makes sense for us to just crank up the scheduler settings now, and investigate the code later.

Optimize

In the “Runtime” tab of the application’s settings in Posit Connect, let’s “Specify custom settings”:

- Max processes: 5

- Min processes: 1

- Max connections per process: 1

- Load factor: 0.00

With these settings, our hypothesis is that each user will be

assigned their own R process, and the metrics should look closer to the

baseline than our previous run5

Benchmark again

Let’s run shinycannon again, and output results to a

different directory, run5-new-settings:

shinycannon recording.log https://rsc.example.com/content/1234/ --workers 5 --loaded-duration-minutes 5 --output-dir run5-new-settingsAnalyze again

Now, back in R, we can generate a new report and compare

run5 to run5-new-settings:

library(shinyloadtest)

df <- load_runs("Run 5" = "run5", "Run 5 new" = "run5-new-settings")

shinyloadtest_report(df, "report2.html")If you don’t want to generate the report yourself, you can view an example here: case_study_report2.html

Just as we

hoped, performance is much improved. After adding processes, sessions

didn’t take as long to run. Because they didn’t take as long to run,

more of them were able to complete in our 5-minute maintenance

period.

Conclusion

In this case study we introduced the optimization loop

workflow and demonstrated how shinyloadtest and

shinycannon can be used together to assess an application’s

performance and guide its optimization.

We ran a baseline test to establish the performance of our application in the single-user case, and then ran a subsequent test to see how it did with multiple concurrent users.

We were dissatisfied with its multi-user performance, and considered whether to improve the application’s performance or simply allocate it more resources. We chose to allocate more resources. Then we benchmarked and analyzed again and observed a satisfactory improvement.

If in the future our application needed to support many more users, we could apply this process again. We might decide next time to invest in the performance of the code instead of just tweaking configuration.